I often tell people that there is little humans can do that doesn’t have an avian counterpart. People who remain devoted to their mate throughout their life are like swans, geese, and cranes. Those who tolerate each other and stick it out for the duration but take separate vacations are more like Bald Eagles. Those who flit from one one-night-stand to the next are hummingbirds. People who focus for long periods on one task are like kingfishers, who may take close to two months to excavate a single nest tunnel, or eagles that continue to work on the exact same nest for decades. Those who flit from thing to thing, never quite settling on anything, are the cowbirds who can’t build a nest at all, and lay their eggs in the nests of dozens of other birds.

I’ve found bird representatives for various political persuasions, sports, hobbies, approaches to housework, and all manner of things. But the one thing I could never even imagine finding a bird corollary for was the iconic group hug on the last episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show. As a handful of readers may recall, the WJM news crew, all sobbing and holding onto one another in a massive group hug, stayed in position as they shuffled over to a desk to grab some tissues. Of course no birds would ever engage in an actual group hug, and if they did, there’s no way that they’d shuffle about, arms or, actually, wings around one another, not letting go as they moved in a tight mass. That would be inconceivable, right?

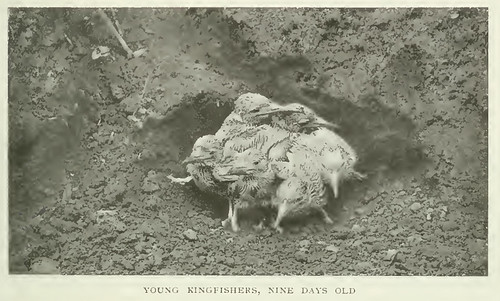

Apparently, my faith in the endless variability and coolness of birds is not as strong as it should be. It turns out that one kind of bird at one point in its life cycle does get into a group hug and shuffles about in a mass together just like on The Mary Tyler Moore Show. Belted Kingfisher adults are not the least bit inclined to watch TV sitcoms or engage in group hugs—indeed, they are one of the more solitary, unsociable birds around. But their nestlings do indeed wrap their wings and wide bills around one another almost exactly like Mary Tyler Moore and friends, maintaining their positions and shuffling en masse if one bird even moves its foot.

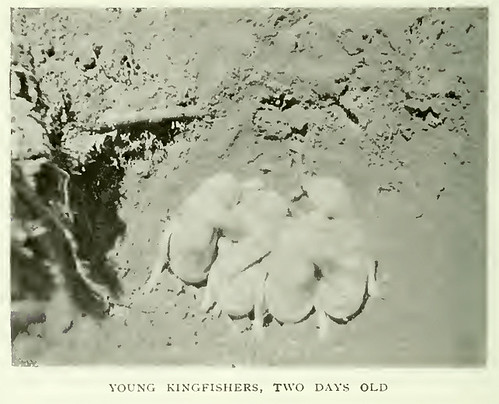

How could such a peculiar behavior originate? Kingfisher legs are so very short that adults barely stand tall enough above the 5-8 eggs in a clutch to incubate them all. Newly hatched chicks are already a bit more spread out than the eggs they came out of, and as they grow, the brooding parent can cover a smaller and smaller portion of their bodies, which start out naked, with no down at all. The tunnel of their nest is so long that the nest chamber stays fairly warm, but until the babies can maintain their own body temperature, they still desperately need to conserve body heat, which they accomplish by means of that peculiar group hug. Of course, only a handful of people have ever witnessed live baby kingfishers at such a young age—usually to gain access into their nest chamber at the end of a long, long tunnel in a sand bank, the entire structure will collapse. But sometime around the turn of the last century, William L. Bailey figured out how to access a kingfisher nest from the opposite side, and made a study of one brood of young kingfishers, which he published in Bird-Lore (2:76–70, 1900). He noted that when the young were about two days old they:

... were not only found wrapped together in the nest, but the moment they were put on the ground, one at a time, though their eyes were still sealed, they immediately covered one another with their wings and wide bills, making such a tight ball that when one shifted a leg, the whole mass would move like a single bird.

|

|