|

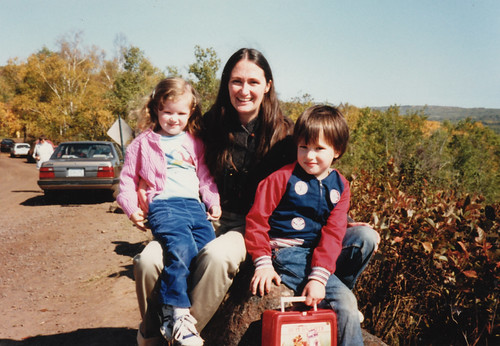

| Me birding at Hawk Ridge with my Katie and Joey on September 26, 1987. My bird lists help me put dates on family photos. |

When I saw and identified my first Black-capped Chickadee on March 2, 1975, I started my life list. Keeping track, one by one, of the birds I've seen in the wild has been one of the most rewarding pastimes of my life.

I've never been particularly competitive about my life list, county list, backyard list, list of birds that have pooped on me, or any of my other lists, even as I love making each list as long as I can. The only time I ever posted a list on the American Birding Association's Listing Central was for my 2013 Big Year total, and I only did that because I'd been in part inspired to do the Big Year thanks to the movie The Big Year. Seeing the totals in Birding magazine was such an important part of the movie that I figured I should do that, too.

Paula Lozano, one of my dearest friends and the first person I turn to whenever I have a tricky gull or shorebird question, does not keep a life list. She's a master birder without listing. And I know quite a few birders with huge life lists who would never consider themselves advanced birders—they've simply had lots of opportunities to go to lots of places with top-notch guides. Whether or not one keeps any lists at all is entirely a matter of personal preference, not in and of itself evidence of skill, commitment to conservation, or anything else. The American Birding Association provides a way for birders to post and compare their lists without any implication that keeping these lists is an essential component of birding—their motto is "A million ways to bird."

Most of my birding friends who don't keep lists choose not to because they bird to get away from the meticulous attention to detail required in their work life, or because listing adds a level of stress, or because after a day of birding, when they get home they want to concentrate on home things, not sit down and labor away on lists. One can take a great deal of pleasure in seeing your first Spruce Grouse ever without feeling any compunction to put it on a list, and for some people, the added layer of paperwork would take away from the enjoyment.

Over the years, I've heard listers encourage non-listers to at least post their sightings on eBird, but overall, those promoting eBird as a way to gather important data about birds haven't seemed to take on the evangelical zeal of a few of those in the opposite camp who outright dislike listing. A few birders seem to think competitive birding or putting any focus on seeing lifers is unseemly, and that their lack of lists is a measure of their purity in enjoying nature.

When I was writing my book, For the Birds: An Uncommon Guide, in 1993, I was inordinately pleased with the final sidebar in the book, for the December 31 entry:

When Russ and I put our family photographs in order, we couldn't recall dates—like one excursion to the Morton Arboretum. Joey was missing a front tooth so it must have been—no, Katie's hair had grown out from her experiment with bunny scissors so it couldn't have been before ... I remembered three Hooded Mergansers in the pond, checked my bird lists, and had the exact date. No one should go through life listlessly.I personally take a lot of pleasure in keeping my own lists, but wouldn't want anyone else to compromise their own pleasure by feeling pressured into listing. That's why I found the pun so pleasing—birding with or without lists should be joyful, keeping listlessness at bay. Even so, my own lists have indeed brought me pleasure, as I noted in that final entry in the book:

As the year draws to a close, many people look through photographs of their past. I pull out bird lists and field notebooks. I seldom record more than date, place, weather, and species, but even that conjures vivid memories—four Buff-breasted Sandpipers running in the grassy park where I walked in solitude after my father's funeral, an adult Bald Eagle flying over the hospital as I held my newborn Tommy to the window, the time Russ photographed nodding trillium as I waited impatiently, antsy to see birds, not flowers. Even as I sighed audibly to hurry him along, my lifer Pileated Woodpecker flew in so close that I felt the rush of air as he landed. I remember a Herring Gull cruising over Hawk Ridge while Katie, one and a half, sat in her stroller. She couldn't pronounce the "s" sound yet, so she pointed up and said "eagull!" A dozen birders automatically pulled their binoculars up—and then gave her disparaging looks for misleading them.

Leafing through my notebooks, I remember other times, other birds. Lists unlock memories of auld acquaintance both avian and human—a lasting record of years of jolly times and friendships and birds and love.

|

| Look very carefully at the exact center of this photo. At the base of the broken birch is my lifer Pileated Woodpecker, here at Hartwick Pines State Park in Michigan on June 5, 1976. |