Today is the day I celebrate every year as Warbler Day. Up

here in Duluth, warbler migration is just kicking in, but in other places I’ve

lived—Chicago; Lansing, Michigan; Madison, Wisconsin; and Ithaca, New

York—warbler migration usually is peaking right about now.

I selected May 11 as Warbler Day because that’s the day I identified

my first warblers ever, in 1975. I lucked into the middle of a big migratory

flock of them. Most warblers are territorial enough by spring migration to get

agitated hearing others of their species singing, so a flock of, say, 7

individuals is likely to have 6 or 7 species rather than several of a single

species. Sure enough, that one flock gave me a veritable rainbow of warblers: Black-and-white,

Nashville, Magnolia, and Black-throated Green.

In retrospect, that flock also

definitely had a Canada Warbler—I was trying desperately to see all the

important field marks of each one, but going back and forth between the bird

and my field guide was tricky because the birds were so actively flitting this

way and that. I saw one that was brilliant yellow with shiny black streaking beneath,

with a bluish gray back with no wing bars. I looked down in my book and found

Canada Warbler, but when I looked up at the bird again, the one where it had

been also had a brilliant yellow underside with shiny black streaking, but it now

had large, thick white wing bars. It cooperated long enough for me to confirm

it was a Magnolia, but the one I first saw there had to be a Canada Warbler even

if I didn’t see it long enough to confirm it for my life list.

I’m sure there

were several other species in the flock as well, but needed more time to study

each one than the active little birds gave me.

Two days later I added another warbler to my lifelist—the

Blackburnian.

Those were the only warblers I was able to identify that spring—I

was just starting out, still new at getting birds into my binoculars and

tracking them, and trying to fix all the critical features of each bird while I

could hold it in view. I clearly remember how frustrating warblers were for me,

but also the thrill when I kept one in view long enough to work through what it

was. By the next spring, I was much better, and my warbler list grew to over 20

species.

The warblers I saw in 1975 may be the first ones I ever

identified, but they aren’t the first ones I ever saw, though I didn’t realize

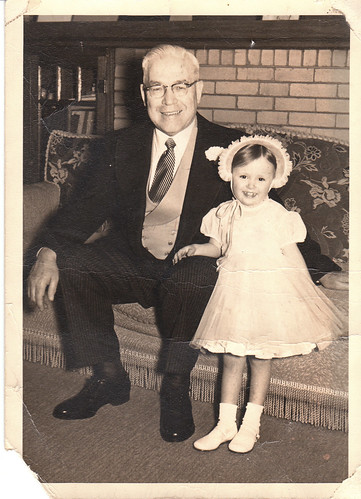

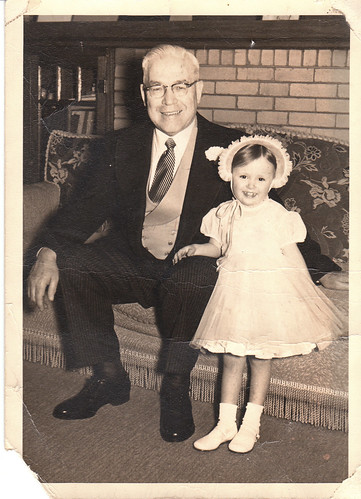

it at the time, because I happened to be a preschooler. It was probably May

1957 when I saw a flock of brilliantly colored, tiny birds in the maple tree

out my upstairs bedroom window in Northlake, Illinois. My mother said they must

be canaries, but they were ever so much more intensely colored, and so much

more active, than the only canaries I’d ever seen—my Grandpa’s beloved pets.

My Grandpa had told me how canaries saved the lives of miners by warning them about poisonous gases—but those heroic little birds actually had to die to save them. So my preschool brain reasoned that these brilliant little birds outside my window must be the angels of canaries that had died saving miners’ lives. When I became a birder and realized those angel birds had been warblers, my childhood fancy made the warbler family even lovelier and more precious to me.

My Grandpa had told me how canaries saved the lives of miners by warning them about poisonous gases—but those heroic little birds actually had to die to save them. So my preschool brain reasoned that these brilliant little birds outside my window must be the angels of canaries that had died saving miners’ lives. When I became a birder and realized those angel birds had been warblers, my childhood fancy made the warbler family even lovelier and more precious to me.

Warblers are challenging puzzles, beautiful spirits, and

wonderfully characteristic of our north woods. Of course, the dark side of

enjoying them on their breeding grounds is the ever present cloud of mosquitoes.

Mosquitoes bite warblers as voraciously as they bite us humans, but in turn the

warblers get quite a bit of protein by gobbling up mosquitoes, inadvertently consuming any human

blood those mosquitoes may have sucked up.

It’s cool to look at warblers rushing through and wonder which might have a tiny speck of protein in their bodies that came from my own blood. It’s satisfying to realize that I am unwittingly supplying at least a trace of nourishment to these luscious little birds that so deeply nourish my soul.

It’s cool to look at warblers rushing through and wonder which might have a tiny speck of protein in their bodies that came from my own blood. It’s satisfying to realize that I am unwittingly supplying at least a trace of nourishment to these luscious little birds that so deeply nourish my soul.