As of today, the Ides of March 2017, I saw my first Black-capped Chickadee 15,354 days ago. I’ve seen more than one chickadee on most of those days and over 200 in a single day on a few Christmas Bird Counts.

I'm sure I haven’t seen an average of 65 chickadees a day over that time, and that's the number I’d need to have averaged to have amassed a million chickadees in my lifetime so far. I would guess I’ve averaged somewhere between 5 and 20 a day over that time, giving me a total of anywhere between 76,770 and 307,080 chickadees seen in my lifetime so far. I’m nowhere near being a chickadee millionaire—a distinction that would be harder to achieve in even a long lifetime of birding than becoming a millionaire in the monetary sense. In terms of chickadee sightings, I’m pretty sure I'm wealthier than Warren Buffett or Bill Gates, but really, the riches we gain from knowing and loving birds, even just our backyard birds, transcend such a silly comparison. When bird experiences make you wealthy beyond measure, there's no measure for comparison with anyone else.

I use Adobe Lightroom for organizing and processing my photos. So far I've tagged 12,142 photos of Black-capped Chickadees, and uploaded 557 of them onto my Flickr photostream. Black-capped Chickadees weigh about 1/3 of an ounce, so there are roughly 96,000 chickadees in a ton. I can legitimately say that I’ve seen close to a ton of chickadees in my lifetime, and possibly as many as three tons, but I've photographed a mere eighth of a ton of them. But who's counting?

Seeing my first chickadee on March 2, 1975, was a life-shifting experience far beyond simple quantification. Ever since then, I’ve thought of my life in two eras: Before Birding and After Birding. When I consider the 8,512 days that I lived before seeing my first chickadee, I wonder what the heck I was paying attention to. I walked to and from school every day from first grade through high school, somehow never once noticing a lovely “Hey, sweetie” song ringing in the trees, or a tiny bird with a relatively long, spiked tail zipping past me as I moseyed on long walks, or an adorably plump white-cheeked black-and-gray bird as I gazed out my bedroom window through the branches of our maple tree.

I did notice some birds. When I was very little, I often looked out our Chicago two-flat window watching pigeons trudging on the gravel-edged street and flying about. When I was four, we moved to Northlake, the working class suburb where we lived until I was in college. My Grandpa pointed out the cardinal's easy-to-learn songs, and so I specifically listened for it.

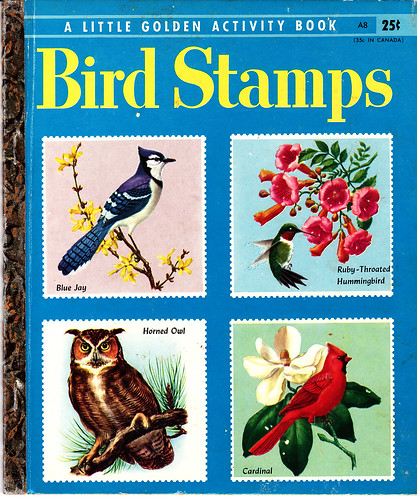

I didn’t recognize any other bird songs except House Sparrows cheep cheep cheep-ing away in our shrubbery or at McDonalds, where I tossed French fries to them, I recognized them from the Little Golden Activity Book, Bird Stamps, that my Grandpa gave me. That’s also how I recognized a magnificent Blue Jay when my family went to Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, when I was 5 or 6. It may have been that book that helped me recognize the robins running on my lawn, too, but I didn’t learn their song until I started birding.

The birds I now know as grackles occasionally hung out in gangs on our lawn—at the time, we called them crows or crow blackbirds. They weren't in the book.

I spent two years on the University of Illinois campus and four years in and near the Michigan State Campus in that era Before Birding. I used to save tidbits of my breakfast and lunch to set on the windowsill of my U. of I. dorm room—plump birds with bright yellow beaks and pretty flecks on their shiny black plumage would fly in at the sound of my window opening to feast on my offerings. By that time, my Bird Stamps book was long gone, and it wasn’t until I started poring over my field guide as a new birder a few years later that I retroactively figured out that they were starlings. At Michigan State, Russ and I took at least a dozen walks in Baker Woodlot—the very place I saw my first chickadee—without my paying much attention at all. I’m sure generic birdsong filled the background soundtrack of many of my spring and summer mornings, but except when a cardinal song infiltrated my consciousness, I was unaware of it.

And then on March 2, 1975, I set out to be a birdwatcher and a miracle happened. I focused—started paying attention—and as it turned out, birds and their sounds were everywhere. Of course, it was still wintry enough that day in East Lansing that it took close to an hour for me to find that first chickadee—the only bird I saw on that walk. I can’t remember how helpful its chickadee-dee-dee calls might have been in drawing my eyes to it, but by April I was finding a great many of my birds by sound, painstakingly figuring out the voices of each species one by one by tracking them all down. And even when they weren't calling, wherever I went, I was suddenly seeing birds.

Ever since that spring, my life has been a rich tapestry of encounters with individual birds. Instead of a generic background soundtrack, I hear a chorus of individual voices. I both notice and recognize birds as I go about my daily life. Wherever I am, I find dear and familiar avian friends and make new ones. Since becoming a birder, my world is richer visually and aurally, and a whole lot friendlier.

In the movie Pleasantville, the characters live in a dull black-and-white world until, one by one, they experience a moment of transformation, and their eyes open to all the colors of what had been dull shades of gray. I’ve always seen a colorful world, but somehow missed noticing, both with my eyes and my ears, a major component of that world for 8,512 days. After living in this whole new world for more than 15,000 days, I still look back at that child—that teen—that young woman. She was blind and deaf to a huge part of the world around her, so I can't help but wonder, what was catching her attention?