Ninety-nine years ago today, my mother-in-law, Helen, was born in Andersonville, the Swedish neighborhood in Chicago. Her mother, an immigrant from Sweden, died just four days after Helen was born, while Helen’s father was fighting in World War I, so one of her mother’s friends took care of her. When Helen’s father returned from the war, he wasn’t in a position to care for a small child, so she remained with her foster mother for several years. When her father married, Helen didn’t want to leave the only mother figure she’d ever known, so she stayed put until her foster mother died. Then she moved in with her father, stepmother, two half-brothers, and half-sister. During the Depression, the children often spent their summers with relatives in Port Wing, Wisconsin, where Helen met my father-in-law. They wrote to each other during World War II, and married after the war.

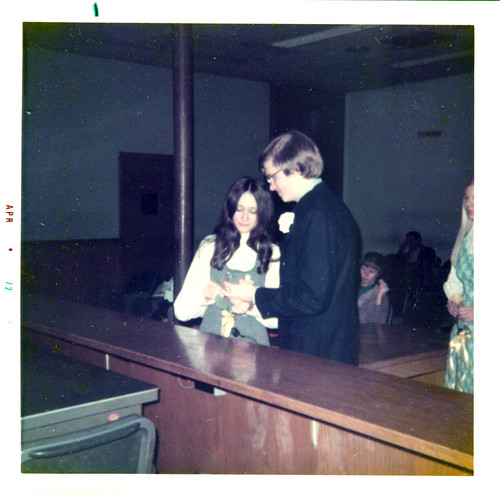

Russ and I started dating the summer before our senior year in high school, and from the very start, his parents made me feel like a part of the family. We started out at different colleges—Russ at Michigan State and me at the University of Illinois—but I switched to MSU when we decided to get married during our junior year. I was on my own at 19 anyway, so my parents didn’t figure into the decision, but nevertheless, getting married so young was more impulsive than we realized. Russ’s parents gently tried to talk him out of it, but 20-year-olds always feel wise beyond their years, and his parents handled it all gracefully and generously. Russ’s mom loved the trappings of beautiful weddings; our cheap, simple wedding before a judge, with just twelve people present counting us and the judge, seemed inexplicable to her. But she never once criticized our choices.

I made my own simple jumper and Russ’s trousers with the same blue denim knit fabric—about as far from traditional wedding garb as one could go. If Russ's parents came to the obvious but erroneous conclusion that we were rushing things because I was pregnant, they never voiced the thought; our first baby didn’t come along for almost ten years.

Russ told his mom to buy me binoculars and a field guide for Christmas in 1974, but she did much more than just that to get me started birding. She took me to lots of birding spots in Chicago, such as the Morton Arboretum, the Little Red Schoolhouse and Crabtree Nature Centers, Baker’s Lake, and various forest preserves. She never kept a life list of her own birds, but she was wonderfully happy whenever I got a lifer. After she and Russ’s dad bought their place in Port Wing, during the time they were fixing it up and then after they moved there, I’d come visit to take long walks through the best habitats, and she was always ready to sit down and hear about the birds I’d seen and heard. She also kept me apprised of all the birds she was getting at her feeders.

From the moment I started producing "For the Birds" in 1986, Helen was my most faithful listener. She especially enjoyed when I referred on the air to my father-in-law as the president of the Port Wing Blue Jay Haters. She continued listening every morning on KUMD until just a few years ago, when her poor hearing made it too frustrating.

I was never a very good day-to-day cook, so for the most part, Russ took over that responsibility. I very clearly didn’t fit his mom’s idea of a housewife, but she never seemed to expect me to be one. Indeed, one time when she and I went to lunch at her friend's house, Helen carried in a bunch of stuff and handed me the container with her freshly-baked cookies. Her friend took them at the door and said they looked wonderful. "Did you bake them, Laura?" Before I could say a word, Helen jumped in and said, "Of course not! Laura has too many important things to do with her life than sit around baking cookies!"

As far as domestic skills go, she considered me her adorably ditzy daughter-in-law, and over the years, I could sometimes see a little smile on her face when I messed up some simple homey task. I probably had that same smile on my face when she misidentified a bird. We were wonderfully well suited, fond of each other not despite one another’s shortcomings, but somehow because of them.

|

| Helen and me in 2014 at the Port Wing Fall Festival |

Russ’s dad died in 1992; Helen continued to live in her house in Port Wing until 2012. During the time she was on her own, she was the most self-sufficient person I’ve ever known. I stayed with her 24-7 at a few points while she was in her 80s and early 90s when she was sick, and when she had a crippling case of bursitis in 2012. That time I spent one full day away doing a Big Day fundraiser starting and ending in Washburn. I got back to her house after 10 pm, when she’d normally be heading to bed, but as I came in the door, she went straight to the kitchen and cooked me up a dinner. I tried to convince her that I was perfectly capable of making my own meal, but despite the pain she was in and her inability to stand straight, she smiled with that familiar twinkle in her eye. I’d spent my day in my own milieu, but now I was on her turf, back to being her ditzy daughter-in-law.

Little by little, her body was growing more frail and dementia was setting in, so we brought her to live with us in Duluth in December 2012. Over these past years, she’s lost more and more memories and become increasingly detached from some of her old interests. She hardly ever looks out at the birds in our feeders anymore, but she can still play and win at Uno when our family gathers at Christmas, and she still figures out some of the Wheel of Fortune puzzles before I do. She reads and does crossword puzzles and jigsaw puzzles every day, makes her own breakfast and lunch (though we have to make sure she remembers), empties the dishwasher, and sets the table. I do physical therapy exercises with her each afternoon, and watch various movies and TV shows with her every evening.

Our old house, with its small rooms, narrow hallways, and tight corners, can’t be negotiated with a wheel chair or even a good walker, so we’re dreading a future when she can’t get by with a cane anymore. But for now, we’re managing surprisingly well.

It’s been very hard for this supremely self-sufficient woman to find herself being taken care of, which makes me sad. But she hasn’t entirely lost her spark of independence. Russ had to go out of town a couple of times in the past couple of months, which meant I cooked our dinners every night. When she sat down, waiting for me to serve, she got that familiar twinkle in her eye, just knowing her ditzy daughter-in-law would do something wrong. And sure enough, I’d forget her toast or her margarine, or overcook the vegetables, or mess up somehow. It doesn’t take much to make her happy. Helen may be 99 years old today, but one thing she will always be able to count on is her ditzy daughter-in-law.