Charles Schulz’s work matured even as I did—Peanuts peaked both in popularity and nuance during the 1960s. When other girls were buying Beatles records, I was buying Peanuts collections. Russ and I started dating in 1968, and he appreciated my interest—almost all the greeting cards he gave me featured Snoopy or another Peanuts character.

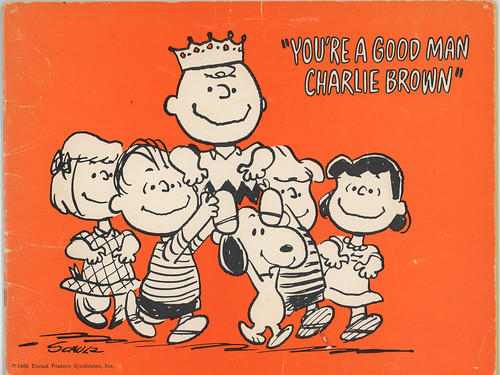

He drew Peanuts characters all over my senior high school yearbook, and took me to see the play You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown at the Civic Theater in Chicago the summer before we went off to college.

Russ also gave me the soundtrack of the Off-Broadway play, which starred Gary Burghoff. I fell absolutely and forever in love with Bob Balaban’s voice, as Linus, thanks to that record, which I played over and over for the rest of the summer. For the first anniversary of our first date, Russ also gave me a plush Snoopy.

That Snoopy and the soundtrack album went off with me to college, and came with Russ and me everywhere we’ve lived ever since. I still have the record album, though I’ve also since bought that recording on CD, too.

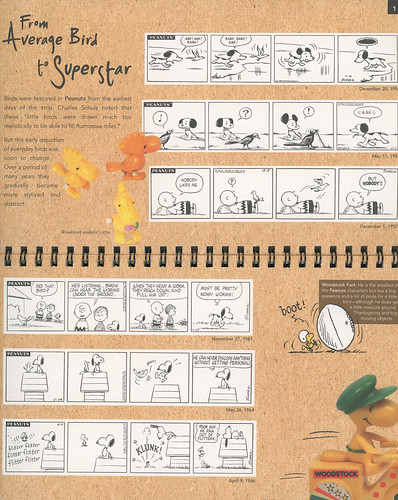

Woodstock wasn’t a character, with or without a name, for the first 15 or 16 years of Peanuts. The first strip to show a bird is dated December 20, 1950, when Snoopy chased a generic bird until it outsmarted him, meaning Snoopy’s awareness of birds originated before I was even born. He watched a generic bird singing on May 11, 1953—he was repulsed when the bird stopped singing to pull an earthworm out of the soil and eat it. On December 5, 1957, Charlie Brown was complaining, “Nobody likes me” when a bird alighted on him momentarily, but then flew off. Charlie Brown said, “But NOBODY!!!”

Looking at that strip and others makes me realize that Charles Schulz was the original inspiration of my social media habit of using far more exclamation points than a responsible editor should, but also affirmed that sometimes accurate emotional expression transcends editorial professionalism.

It wasn’t until 1966 or so that a bird resembling Woodstock appeared in Peanuts. At first, the little guy was a generic bird, not an actual character, and Schulz hadn’t decided on any particulars about it. It was 4 years after that that Schulz gave him the name Woodstock, on June 22, 1970.

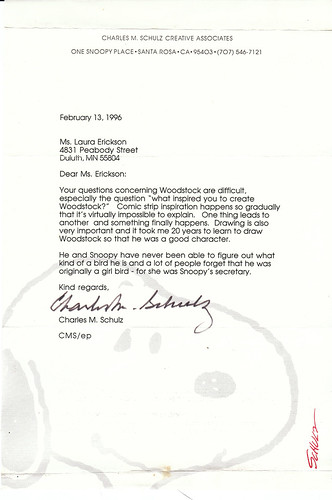

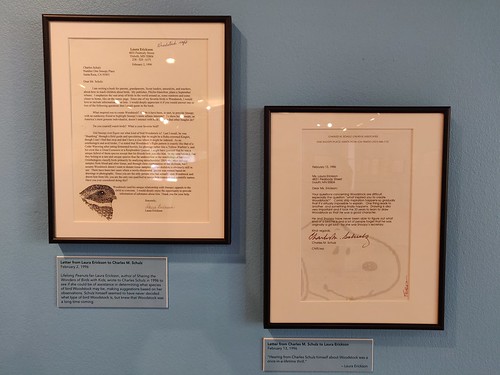

Because I loved Peanuts so much from my earliest childhood through my entire adulthood, it was natural that I’d mention Woodstock in my book Sharing the Wonder of Birds with Kids. While I was researching it in 1996, I wrote to Charles Schulz himself, asking about Woodstock. I wrote:

Did Snoopy ever figure out what kind of bird Woodstock is? Last I recall, he was “thumbing” through a field guide and speculating that he might be a Ruby-crowned Kinglet, though I can’t find that strip and don’t have a clue where it might be indexed. As an ornithologist and avid birder, I’ve noted that Woodstock’s flight pattern is exactly like that of a Cedar Waxwing after eating fermented berries, his plumage rather like a Yellow Warbler’s, and his crest like a Great Curassow or a Resplendent Quetzal. I might have guessed that he was a unique hybrid of these species except that his friends look just like him. So my conclusion is that they belong to a rare and unique species thus far undescribed in the ornithological literature. Ornithologists classify birds primarily by analyzing mitochondrial DNA and other cellular samples from blood and other tissue, and through close examination of the skeleton, but I assume Woodstock doesn’t want to donate tissue samples and his skeleton is obviously still in use.

There have been rare cases where a newly-discovered species was named based on drawings or photographs. Since you are the only person who has actually seen Woodstock and drawn him from life, you are the only one qualified to assign him common and scientific names. Have you ever considered doing this?My letter was dated February 2, and I received a response from Charles Schulz dated February 13. He wrote that Woodstock “and Snoopy have never been able to figure out what kind of bird he is and a lot of people forget that he was originally a girl bird—for she was Snoopy’s secretary.”

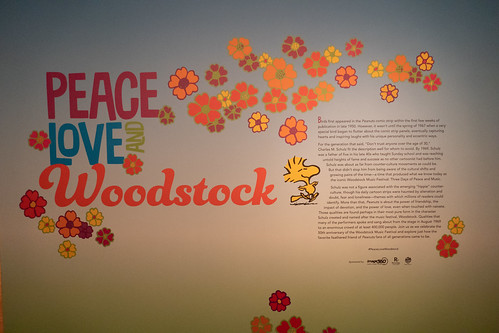

I was thrilled beyond measure. I used the information in my book and hung the letter from Charles Schulz up in my office. There it remained until just last year, when I received a letter from the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California. For the fiftieth anniversary of the Woodstock music festival, which was where Charles Schulz took his little bird character’s name, they put together an exhibit titled “Peace, Love, and Woodstock.” And oddly enough, though Charles Schulz disposed of most of his fan mail, my letter was filed away with a handwritten “Woodstock info” added to the top. The museum staff wondered if Schulz had ever responded. So I scanned my letter from him to send to them. They then wondered if I’d be willing to let them borrow the original for the exhibit. Of course I said yes and sent it off. When the exhibit was set up, Benjamin Peery, the museum registrar, sent me photos of the correspondence hanging in the exhibit.

Thrilling as that was, it led to a most natural yearning to go to Santa Rosa to see the exhibit up close and personal. A Washington Post article published in the Duluth News-Tribune and a segment on CBS Sunday Morning made me yearn even more to see it. So Russ and I decided to take a trip to California, which we did just last week. We of course had to bring my 50-year-old plush Snoopy along, and also his little Woodstock doll, which my life-long close friend Karen, who was also my college roommate, sent after our first baby was born.

We went to the museum twice—on Sunday, September 29, we looked through the museum on our own, and on Monday, September 30, a museum archivist gave us a personal tour, which was utterly delightful in every way. The Woodstock exhibit traced Schulz’s use of birds in the cartoons from the beginning through his fine-tuning of the Woodstock character,

exhibited a few of the cartoons which showed Snoopy and Woodstock trying to figure out what species he was,

and included lots of other Woodstock strips, other artwork, and memorabilia. Just about every time we walked into the room with my correspondence on display, someone was actually reading the two letters, which was gratifying to say the least.

I love that a quarter century ago, Charles Schulz read a letter that I wrote, and I love that he thought it significant enough to both answer my letter and then file it away. I love that the bird character he created is still beloved today, and that my little correspondence with him became part of an exhibit specifically about that bird, coincidentally and magically marking my own beloved Snoopy’s 50th birthday. I lead a freakishly happy and rich life, all because of birds. Who could ask for anything more?