I've had cataracts my whole life, though I never knew that until the 1980s, when I bought my first top-line pair of binoculars. They cost over $800, which amounted to pretty much our family's entire discretionary income that year, so I naturally wanted to be sure they'd been worth it. I kept looking at things near and far, and then checking how well aligned they were and how perfect the optics were by closing one eye and then the other. Oddly enough, everything was a bit dimmer and more yellowish-brown through one eye than the other. I was afraid the binoculars might be defective, which would involve sending them back and waiting for a replacement, but just to be sure, I reversed the barrels, looking through them with the opposite eyes, and discovered that it wasn't the binoculars—it was my eyes. One was dimmer than the other. I asked my ophthalmologist at my next visit, and he said that I had congenital cataracts, with that eye much worse than the other.

Ophthalmologists wait until the cataracts are what they call “ripe,” and as old as mine are, they weren't ready until this fall. As Hamlet said, “The ripeness is all!” My ophthalmologist always does the non-dominant eye first, which in my case is the right one. She'll do the left eye in two weeks.

I had to make one major decision before surgery—what kind of lens I want implanted. The standard, which was the only option for a long time, is a monofocal intraocular lens focused for distance; now you can choose monofocal lenses focused for intermediate or near vision, and some people choose one for distance for one eye and one for closeup or intermediate for the other.

And nowadays, multifocal intraocular lenses are also available, working much like bifocals or trifocals. One of my close friends has ReZoom multi-focal lens implants, which have concentric circles with a different correction in each. The one problem she notices is that in certain light situations, she looks through two rings of correction and can see a bit of a shadow along a sharp edge. But her brain has learned to accommodate for that. Those rings also can cause glare around bright lights, and seem to affect her distance perception, so she doesn’t like to drive at night.

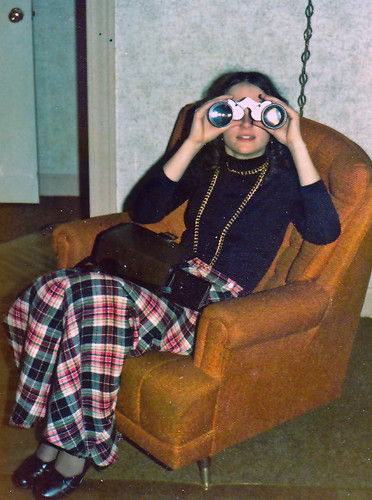

Me, I’m going with the monofocal distance vision in both eyes. I’ve been nearsighted my whole life, so this will take some adjusting for me—for the first time ever, I’ll need glasses for mid- and close-up vision, and will have to get in the habit of wearing reading glasses on a chain like a stereotypical little old lady in tennis shoes.

I know lots of people who’ve had this surgery, and almost everyone has been pleased with the results. Cataracts have a brownish discoloration; when that’s gone, everyone says the world will look brighter again. For me, that brightness may be more surprising than it is for most, because my congenital cataracts almost certainly made colors appear off my entire life. I can’t wait to see what Cuban Todies really look like!

As both a birder and a photographer, I’ll have to deal with some practical issues. This year’s Duluth Christmas Bird Count is on the 14th, after my right eye should be pretty well healed, but a few days before my left eye is done. That means the two eyes' vision will be wildly divergent, one focusing near and one far. For a while before getting bifocals, I used to wear a single contact lens, giving me that kind of vision—I adjusted pretty quickly to focusing on near things with one eye and on distant things with the other. On bird count day my right eye will focus on the birds, and I’ll be able to see my cell phone to record birds with the eBird app using my left eye. But to use my binoculars, I’ll have to set their diopter adjustment for the different focal lengths of my two eyes. After the second surgery, I’ll have to redo that again when both eyes have close-to-identical focal lengths. And after the second eye is done, I’ll have to adapt to putting on reading glasses in the field when I want to use eBird or review photos via the LCD screen on my camera.

To take those photos in the first place, I’ll have to make an adjustment on my camera's eyepiece for my new vision. I don't review my photos on the screen very often in the field, so I'll focus the eyepiece for my vision without glasses—it'll be wonderful to do all my actual birding—watching birds and using both binoculars and camera—without glasses. Getting older has some unpleasant costs, but cataract surgery will almost certainly make my outlook the brightest it's been in my whole life.