Fifty years ago this week, on April 22, 1970, schoolchildren and teachers from kindergarten through college, families, and all kinds of clubs and organizations banded together throughout the United States to celebrate the first Earth Day, which was the brainchild of Wisconsin’s own Gaylord Nelson. He said, “The objective was to get a nationwide demonstration of concern for the environment so large that it would shake the political establishment out of its lethargy and, finally, force this issue permanently onto the national political agenda.”

Within three years, Congress passed the Environmental Policy Act, Endangered Species Act, Clean Air Act, and Clean Water Act. How very proud Gaylord Nelson must have been! Unfortunately, that Earth Day and its aftermath also shook many industries out of their lethargy, and some, including the Koch Brothers, immediately started banding together to fight these laws. Thanks to them, people were suddenly ridiculing such endangered species as the snail darter fish and the Spotted Owl, and decrying regulations that were designed to reduce the amount of mercury and other poisons and known carcinogens in our air and water.

Just last week, the Trump administration’s EPA directors loosened the rules on mercury and other toxic pollutants, taking advantage of the pandemic, when most people aren’t paying much attention, reasonably assuming that a responsible federal government would be entirely focused on public health right now.

As a college freshman at the University of Illinois, I got involved with Earth Day, though I had no clue what it was really all about. Sure, I wanted to help Bald Eagles, Osprey, Peregrine Falcons, and California Condors. But I couldn’t even imagine that anything like these birds could actually exist, at least not wild and free in any place I could go to. These and other endangered creatures were what I thought of as zoo animals. Sadly, this Chicago girl had absolutely no sense of wildness beyond the Chicago’s forest preserves. There is no way I could possibly have imagined that there could exist a real-live woodpecker that looked like the Woody Woodpecker I’d seen on Saturday morning cartoons, much less that I would ever be able to live in a regular house in a regular neighborhood where this enormous and exotic woodpecker would come to visit.

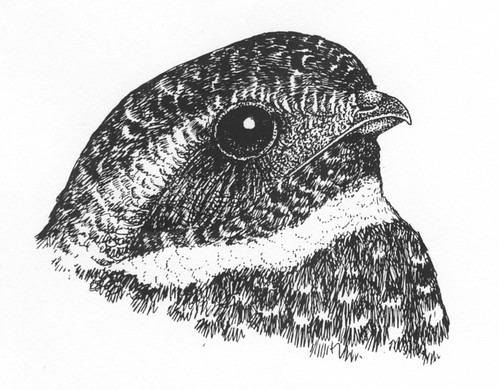

When I got my first field guide for Christmas in 1974, I immediately got fixated on the Pileated Woodpecker.

The Ivory-billed was bigger and even more exotic, but the field guide said it was “on the verge of extinction.” The range map showed the Pileated all over the eastern half of the country, and in a big swath of the West as well—I should be able to find that one eventually, right?

I stared at the picture over and over during the following years, and finally saw my first Pileated Woodpecker a full six years after the first Earth Day, on June 5, 1976, at Hartwick Pines State Park in Michigan. Russ even managed to get a photo of the splendid bird, though it's pretty tricky to find it.

Later that month, Russ had a meeting in Savannah, Georgia, and we came upon a noisy family of Pileateds while we were picnicking in a Georgia state park. To remember those splendid experiences, we bought the full-sized Audubon print of a Pileated family that year. It has hung in our living room, wherever we lived, ever since.

But Pileateds were few and far between most of the time during my early years of birding. My best place for spotting them was up in Port Wing, Wisconsin, when we visited Russ’s parents, but even there it was easier to hear a distant one than see one up close and personal.

Russ and I moved to Peabody Street in 1981. The first couple of decades, they were only rarely seen in our backyard, but in the early oughts, they started being much more regular. One male started visiting my window suet feeder quite a lot in 2004. I called him Jeepers.

Some years one or a pair have appeared in my backyard virtually daily. Suddenly I was getting photos and even videos, including my prized possession, a photo of a male sticking out his long, long tongue.

But 2020 happens to be the first year in a while that I didn’t see a single Pileated on Peabody Street during all of January, February, and March. I had a heart attack in January and so was more stuck at home than usual,

needing the soothing presence of birds right during a winter when they were few and far between at home. I didn’t see a Pileated Woodpecker during April, either, until yesterday, when a pair turned up out of the blue, calling to each other and visiting a lot of our old trees.

As if to honor the fact that Earth Day is this week, the male even spent quite a bit of his time literally down to earth, feeding on and beside the dead birch trunks lining our raspberry patch in the back of the yard and on the ground beneath one of our neighbors' large maples.

The male also visited a couple of my feeders.

Even when they turn up daily, I cannot see or hear a Pileated Woodpecker without a deep and thrilling sense of satisfaction—a feeling of well-being down to my very core—something even more precious during a time when health and safety are so precarious. I may be spending my every minute on Peabody Street for the duration, but I’m hardly alone, not with my husband, son, daughter and son-in-law, and my little dog Pip sheltering here, too, and a grandchild coming this summer. The joys of backyard birding are a perfect icing on this splendid if fragile cake.

Knowing how precarious life is, and how precious this earth and its day-to-day treasures are, raises my commitment to protecting them. Fifty years after that first Earth Day, when I’m ever so much more aware and knowledgeable about wildlife and the environment and how important clean air and water are to my beloved family’s existence, I’m feeling more committed than ever to protecting this beautiful and fragile Earth.