|

| I saw my very first Sandhill Cranes with Bob Hinkle on a field trip to Rose Lake State Wildlife Area in Lansing. |

I’d read some Thoreau in high school and learned a little about ecology during the lead-up to the first Earth Day when I was a college freshman, but that was all theoretical. My mind swirled through a cloud of good feelings about nature and bad feelings about pollution, but I had no concrete way of understanding any of it. Thoreau wrote a lot about birds in Walden, but I knew nothing at all about any of the birds he wrote about. Ecology seemed so clear and obvious from the teachers’ education packet I got for free from McDonalds, with its wonderful overhead projector sheets, ditto masters, and other cool teaching materials, but the fourth-grade level information on the materials were all brand new to me, and I had no deeper understanding of anything beyond them.

It was Bob Hinkle’s class that showed me just how abysmally ignorant I was about plants and animals, how they interact and are interdependent, and what ecology actually means. It was a fantastic introduction that inspired me to stay in college for two years of grad school. I’d take botany, mammalogy, ornithology, herpetology, entomology, and aquatic entomology, and more of Bob’s classes, which gave me a framework on which to hang all the scientific information I was picking up and a lot more time outdoors learning the local plants and animals.

And on top of all that, Bob’s literary bent put all this new information into context in wonderful ways. He read much of Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac aloud to us so vividly that to this day, 46 years later, I have never once heard woodcock dancing in the sunset sky without thinking of Leopold’s words as said in Bob Hinkle’s gently expressive voice.

Bob’s students ahead of me were creating a lot of slide-tape programs, melding music and words with photography. I created a few short ones, taking pictures of toads and dragonflies and trees and flowers. I couldn’t afford a telephoto lens, so it would be three decades before I started taking any bird photos, but since then, I’ve developed dozens of presentations about birds which I’ve presented in 30 different states, in venues from Harvard for the Brookline Bird Club, to Tucson for the Southeastern Arizona Birding Festival to Sacramento for the Central Valley Birding Symposium to Maumee Bay State Park in Ohio for the Biggest Week in American Birding festival. When a program goes really well, I still think of how much Bob Hinkle’s inspiration is behind it.

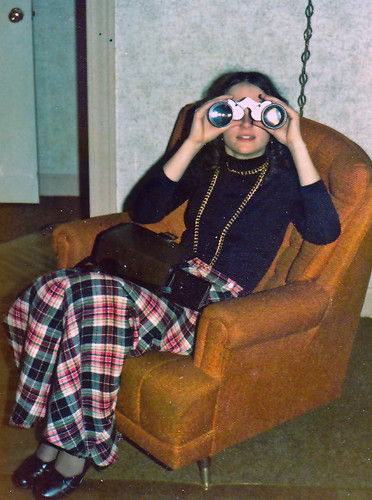

It was my taking Bob’s class that inspired Russ to tell his mom to buy me my first pair of binoculars. In April 1975, after I’d been birding a few weeks, Bob organized an excursion to Natural Bridge, Virginia, for a big meeting of the Association of Interpretive Naturalists. The meeting itself was splendid, but what I remember is Bob showing me my first White-throated Sparrow, with him interpreting the song as Old Sam Peabody, Peabody, Peabody. I’d never imagined such a thing!

Bob pointed out Turkey Vultures on that trip but I didn’t add them to my life list because he explained their flight pattern in comparison to hawks, and I’d never seen a flying hawk, either, so didn’t think I’d necessarily recognize a Turkey Vulture on my own. (Bob became the famous official Turkey Vulture spotter at Hinkley, Ohio, a position he held for years, so I'm very happy that I saw my first vultures with him.) At our campground, I heard what Bob told me were a Chuck-will’s-widow calling and a Pileated Woodpecker drumming, but I didn’t see either bird. This was my bird-watching life list, so I waited for an actual look.

Yes, taking classes and trips with Bob Hinkle taught me just how ignorant I was in a way that didn’t discourage me but inspired me to get out there and learn as much as I could. I aspired to be a real naturalist like him and like so many of my fellow students in his class became, like Wisconsin’s famous David Stokes, but once I started watching birds, I was simply too focused and monomaniacal. Even if I didn’t ultimately become a naturalist, what I did become, in a serious way, all evolved directly from that first class from Bob Hinkle.

I reconnected with Bob a couple of decades after those classes, when he was the superb Chief Naturalist of Cleveland Metroparks, and we’ve crossed paths a few times. I’ve been lucky to tell him how much he means to me. At this terrible time, when so many of our lives are in limbo, we might at least be able to think of the people whose gifts were vitally important to our lives. Be safe and well, dear reader.