In 1986, when I started producing For the Birds, I was the mother of a 4 ½ year old, a 2 ½ year old, and a 7-month-old.

Over the years, the three of them grew up, and in the years since my third baby turned into a toddler, there hasn’t been a single baby nestled into my corner of Peabody Street.

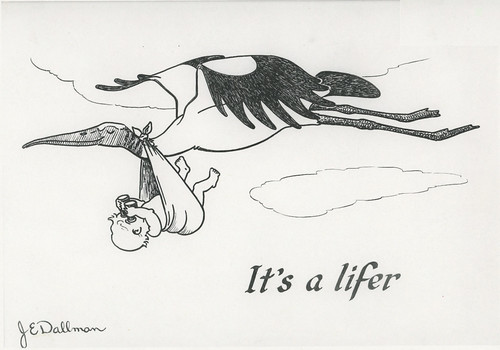

That is, not until just last week. I of course am not the mother—this time around, I’m the grandmother, meaning I get all the joy and fun with none of the physical exertion and pain or profound obligations of parenthood.

I spent so much time watching my backyard nesting birds this year, and thinking about how many hours various birds sit still when incubating eggs or brooding young nestlings, that now, when I hold the baby, I can see how well-adapted I’d be as a female chickadee or wren. Apparently my one superpower is an ability to sit still for hours when a baby is involved, not feeling any kind of urgency to do anything at all except the quiet, still task at hand.

I do respond instantly if a diaper needs changing. Birds don’t do diaper changes—baby chickadees and wrens package their messes in something simpler and more biodegradable than diapers—fecal sacs, which they virtually always produce right after eating a meal, meaning whichever parent was there for the feeding will notice and carry it off to dispose of just as quickly and efficiently as I deal with messy diapers, only without burdening any landfills or sewage treatment facilities.

No one knows for sure what birds think about as they incubate eggs or brood young, and truth to tell, I seldom know what I’m thinking about as I hold this new little nestling—I fall into a reverie and lose all track of time.

This time around, it’s apparently not as hormone-based as with previous Peabody-Street babies, which is rather owlish of me. When rehabbers receive an orphaned baby owl of most species, they virtually never feed it themselves, because the owlet is too likely to imprint on humans. Instead, the rehabbers put it in with an adult owl of that species of either sex, and the adult broods and feeds it, even though it hasn’t gone through any of the courtship and nesting behaviors that would influence its hormonal state. In my case, there’s at least an evolutionary reason to be nurturing, in terms of increasing the likelihood of my own genes surviving into the future. For foster parent owls, not so much—they simply rise to the occasion as I hope I would if I were confronted with a baby in need, even if it wasn’t a baby who shared 25 percent of my genetic code.

I started lists of the birds each of my own babies “saw” if they were awake and pointed in the right direction while we were still in the hospital. The first birds for my sons, both born in Octobers, were migrating Bald Eagles. First for my December-born daughter was the Black-capped Chickadee. Because of the pandemic, I wasn’t allowed in the hospital this time, but the first birds I saw out my dining room window while holding my grandchild were a baby wren and its parents, taking turns feeding it. That was as lovely as it seemed auspicious.

We’ve also seen plenty of chickadees, Blue Jays, hummingbirds, Red-breasted Nuthatches, crows, and pigeons, and I’m already envisioning all the places I want to take this little guy to where we can enjoy birds together in the murky future after the pandemic is over.

Being the kind of person I am, whether it’s closer to an owl, chickadee, or wren, I’m having trouble focusing on anything except my grandchild these days. A baby is a joyful distraction for sure, but a distraction nonetheless.

Birds can't afford distractions, and sure enough, only a very few species of birds, including swans, geese, cranes, crows, and quite possibly Blue Jays, stay in contact with their own young year after year to have at least a clue that they’ve become grandparents, and even they don’t meet their grandchildren while the parents could actually use some support—if they meet them at all, it’s in late summer or fall. When grandchildren birds were being hatched and going through their nestling stage, those grandmother birds were producing new babies of their own. I’m done producing new babies, so I can provide a bit of support for my daughter and son-in-law while enjoying my grandchild and introducing him to the big world of birds. I’m hoping against hope that life in your neck of the world is as rich and lovely. Stay safe and well, dear reader.

|

| My daughter and son-in-law are private people, and I've promised to keep details about their child private. |