Recognizing birds is an essential skill for a birder, and as the author of the American Birding Association’s Field Guide to the Birds of Minnesota, I’m supposed to be an actual authority on bird identification.

But important as recognizing birds is, it’s never been my primary interest. When I was a teacher, recognizing my students was essential, too, but hardly the point. On the first day of school, back in the days when 1-hour film development was a new thing, I’d bring my Olympus camera, loaded with a new roll of film, take a picture of each child, get them developed after school, and take the photos home to construct an identification guide for each class.

In the way that I needed to learn a whole new batch of birds when Russ and I first went to Arizona, I needed to know each student’s range to put them in the correct guide: the Field Guide to Mrs. Erickson’s 6th Grade Science Class had an entirely different set of students than the Field Guide to Mrs. Erickson’s 7th Grade Math Class.

In the classroom, the official range map—my seating chart—was very helpful, but in the same way that individual birds can sometimes be found out of range, occasionally a couple of kids would swap seats to try to throw me off. I couldn’t focus on a lot of elements of plumage—whatever a child was wearing in the first photo was bound to be different the very next day. Through the first week, I’d add helpful “field marks”—especially vocalizations and behavior—to cement my memory of each child. But as with bird identification guides, my field guides to my students quickly became extraneous as we fell into a new year of math or science or reading or music.

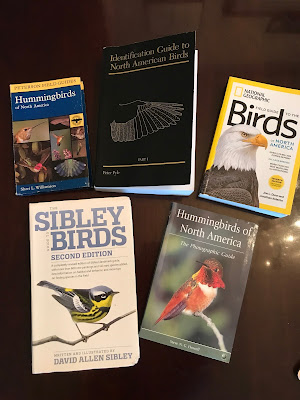

At this point, the birds I find in Duluth are usually ones I recognize as easily as I recognized my students a few weeks after school started. But now and then, even today, I need to focus on identification, cracking out field guides and even more specialized resources.

The hummingbird coming to my feeder right now is a case in point. The vast majority of hummingbirds appearing anywhere in the eastern United States are Ruby-throats. In spring and summer, I hardly even glance at those I see anywhere around here unless I'm trying to photograph them. Having a lot of experience does mean that I can take in a lot of details efficiently, but still, if there were an outlier hummingbird during the time when so many Ruby-throats were about, I could very easily overlook it, in the same way that if a Carolina Chickadee ever worked its way to Duluth, chances are I'd never notice unless it was a singing male.

I've seen one probable Rufous Hummingbird in northern Wisconsin on August 11, 2007. I only saw that one because the homeowner called me telling me there was a "weird" hummingbird with all the Ruby-throats at one of his window feeders. I didn't get confirming details to exclude the rarer possibility that it was an Allen's Hummingbird.

|

| The August 11, 2007 bird in northern Wisconsin. I'm guessing this is an immature male because of how evenly distributed the "spangles" on the throat are. |

A handful of Allen's have appeared here and there in eastern states, but none have ever been identified in Minnesota—comparing their range map with that of the Rufous suggests why.

|

| Traditional range map of Allen's Hummingbird |

|

| Traditional range map of Rufous Hummingbird |

The Land of 10,000 Lakes has had our share of outlier hummingbirds over the years—Calliope, Costa's, Rivoli's, Anna's, and Mexican Violetears, along with the one that has appeared most often, the Rufous Hummingbird.

|

| The hummingbird that appeared at my feeder from November 16 –December 3, 2004 |

It’s important to know for sure who the one showing up on Peabody Street right now is, because the likelihood of survival as November proceeds is much more probable if this is a Rufous Hummingbird than any other species. Why? Rufous Hummingbirds breed the farthest distance from the equator of any hummingbirds. In spring, the main population migrates north along the Pacific slope, they breed in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, and then work their way south along the Rocky Mountains before they get to the American Southwest and finally to their wintering grounds in southwestern Mexico.

|

| This Rufous Hummingbird is exactly where they belong in October, in Mexico. I photographed him in 2006. |

Outlier Rufous Hummingbirds sometimes appear in the eastern states, especially during fall and winter. Most avian outliers end up dying without producing young, but individual Rufous Hummingbirds wintering in the United States are increasing in number, meaning these outliers must be passing their genes on to new generations. Normal Rufous Hummingbirds may now be at a disadvantage as extreme hot temperatures and droughts grow ever more common and as tropical deforestation damages their winter habitat, giving the outliers an evolutionary advantage.

It’s fairly intuitive that hummingbirds wintering in the Southeast can survive winters down there, but we’re also seeing individual Rufous Hummingbirds surviving entire winters in Ohio and Pennsylvania, even with subzero temperatures. Confirming the Peabody Street bird's identity helps us understand changes in Rufous Hummingbird migration patterns in recent decades, giving us a glimpse at the species' evolutionary biology in real time.

|

| Hummingbird bander Nancy Newfield examines the bill of a Rufous Hummingbird with a magnifier. Taken in Louisiana in August, 2002. |

|