A few weeks ago, I created a list of my favorite birds of all time. A 12-way tie for 5th place put 16 species in the Top Ten. I knew I’d reconsider even as I was making the list, and sure enough, it did not take long to bump another into what now is a 13-way tie for 5th place. That happened the moment I saw a Pine Grosbeak at the Sax-Zim Bog on Sunday.

Part of the reason the Pine Grosbeak is a favorite is how extraordinary my very first sighting was, in December 1977 as I walked from Russ's and my apartment toward Picnic Point, my favorite birding spot in Madison, Wisconsin. I was hearing an unfamiliar pretty, warbled whistle and started whistling back. The sound seemed to be coming toward me faster than I was walking toward it, and when I reached the woodsy shoreline around University Bay, I saw a lovely robin-sized, grayish bird with soft bronzy crown and rump fly into a bare branch up ahead, looking directly at me as I whistled. It stayed in the branch as I walked to the edge of the trees.

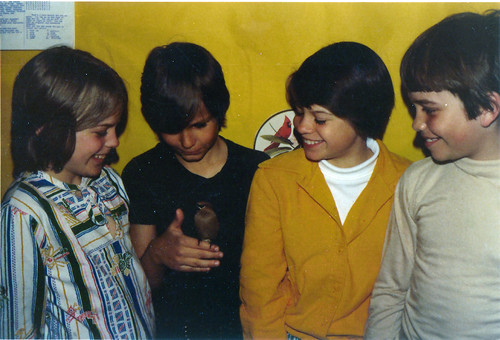

I have no idea what impulse led me to take off my glove and raise my hand, but the bird apparently was moved by a similar inexplicable impulse and instantly flew right to me, alighting on my finger! It was too magical a moment to quantify—I don't know whether the bird remained there for 5 seconds or 5 minutes. When it finally flew back into the trees, it stayed close, moseying along companionably as I walked toward the Picnic Point entrance. I figured, as a fairly novice birder, that this bird, belonging to a very sociable species, was lonely, preferring even an inappropriate companion to being left alone. As I became more familiar with the literature, I read in all kinds of species profiles that among the defining characteristics of Pine Grosbeaks are their approachability and tameness.

Over my lifetime of birding, other lifers have alighted on my hand. When my sister-in-law Jean and I took a trip out west in 1979, my very first Canada Jay landed on my hand and head at our camping site. I’d already seen Steller’s Jay, Clark’s Nutcracker, and Pygmy Nuthatch in Colorado that same year, and on my trip with Jean, those still fairly new-to-me birds also alighted on my hand. But these species were notorious for mooching at campsites back when it was still legal to hand out peanuts to them, and they all made sure I was holding food before they approached. For them, I wasn’t a companion—I was a mobile bird feeder.

I’m sure my lifer Florida Scrub-Jay—seen in April 1999 and #600 on my life list—would have alighted on my hand had I offered it peanuts, a practice still legal at the time at Lake Kissimmee State Park, as it was in 2006 when they delighted our whole family.

In 2005, my lifer Island Scrub-Jay alighted on my hand. That was during a post-convention field trip following an American Ornithologists’ Union meeting. Scientists at the research station we visited on Santa Cruz Island, one of the Channel Islands off California, were regularly feeding them and handed out peanuts for us to give them.

Plenty of other approachable birds have alighted on my hand for food—chickadees, of course, but also Tufted Titmice, Red- and White-breasted Nuthatches, Pine Siskins, and probably one or two more, but none except chickadees were cooperative enough to provide photo-ops.

During the time we lived in Madison, both species of kinglets also alighted on my finger, but in those cases, the birds were manically searching for food on frigid mornings in early migration. I don’t think they even realized I was a living being—just a thick bit of substrate in a tangle of shrubs.

To this day, that Pine Grosbeak remains unique—the only bird ever to alight on my hand with intention, making eye contact, without any expectation of food or any other tangible reward.

That magical moment provided a spark for my love affair with this pretty bird, but even without it, the bird’s beauty and hardiness make it special. Over much of their North American range, adult males are carmine red bordering on deep pink, the color especially intense on their crown and rump. That lovely color is set off to perfection by their white wingbars, sometimes tinged with pink, white-and-pinkish edging on dark gray flight feathers, beautifully patterned back with gray chevrons scattered on a pink background, and soft gray undertail coverts and lower belly feathers. When fluffed up against the cold, soft gray insulating down feathers often peek through the pink here and there. And the dark eyes are bordered with black, giving them an exotic Elizabeth Taylor eye-liner effect.

Young males and all females have the bronzy or yellowish head and rump that my lifer did, a color combination that may not be as arresting as the adult male’s plumage yet has a soft loveliness of its own.

But prettiness isn’t the primary factor I use in selecting favorite birds—Indeed, I may consider the Cuban Tody to be the most adorable bird in the known universe, but it isn’t in my Top Ten. I got to see it several times when I went to Cuba in 2016, and the anticipation did not exceed the actual event, but looking at even a gorgeous bird for at most a few minutes at a time with a birding group is just not the same as spending time alone watching and even interacting with it. (That's why I'd love to go back to Cuba to spend a week or more pretty much on my own in tody habitat.)

When I look over the 17 species that did make my list, every one of them includes individuals I’ve made eye contact with, and 11 are birds I’ve held in my own hands, mostly when I was a rehabber. I did rehab a couple of Pine Grosbeaks way back when—people brought them to me after the birds had struck windows. When a window-struck bird is calm and easy, it's usually a sign of a concussion or other serious head injury. But Pine Grosbeaks can have no head injury at all and be easy to handle—like waxwings, they seem to thrive on company, and even a mere human can serve in a pinch.

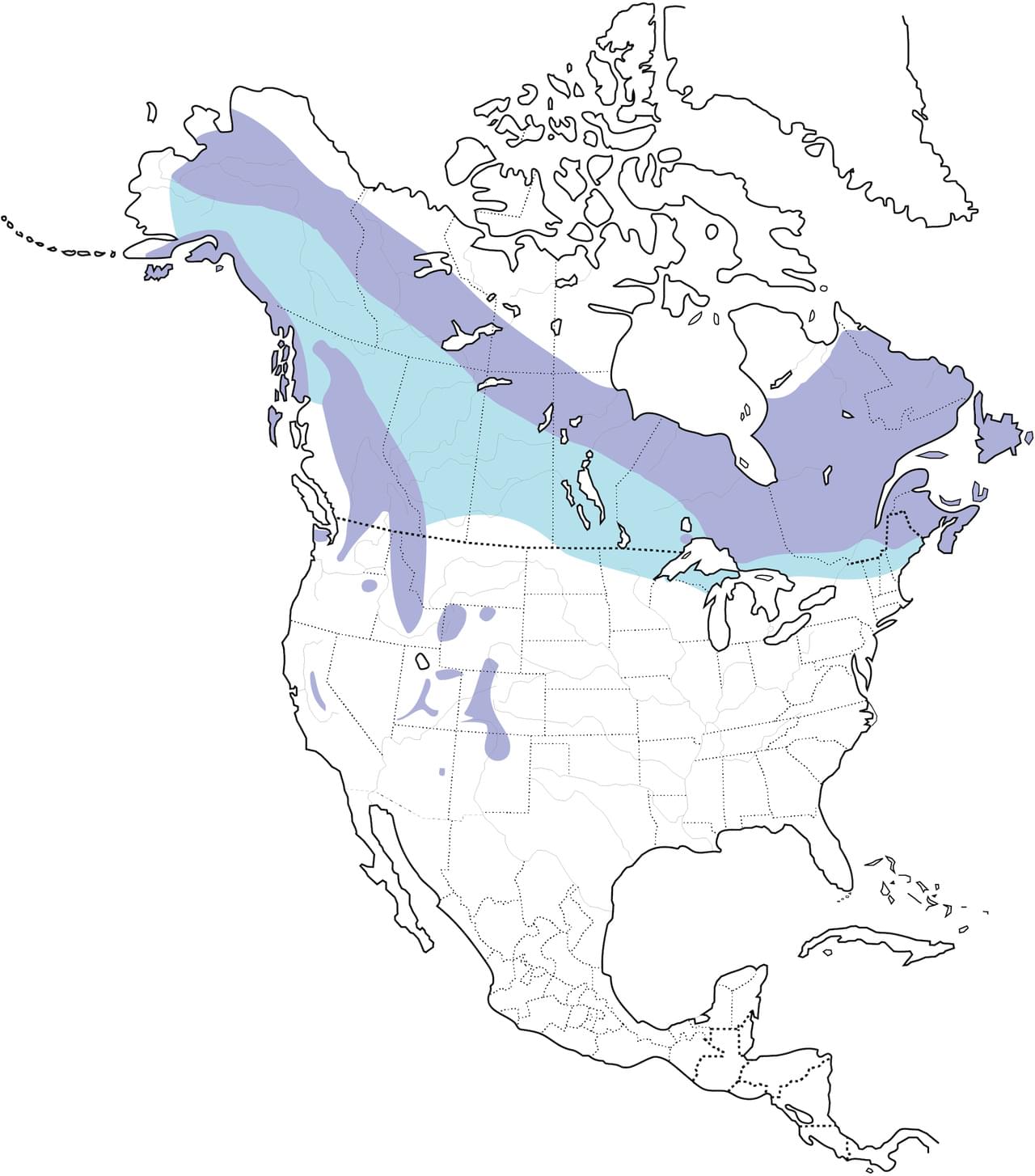

Pine Grosbeaks breed in northern Maine and across a wide swath of Canada and Alaska, and down the western mountains. I recorded them singing in the Sierra Nevadas when I took the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s sound-recording workshop in June 2001.

Pine Grosbeaks are year-round residents throughout their breeding range, but they’re found here in the Midwest only in winter. Many work their way south every year—some years more than others, and in "irruption years" they wander further south than the range map indicates. In my early birding years, I saw them in the Chicago area as well as southern Wisconsin.

I still see Pine Grosbeaks just about every year in the Sax-Zim Bog, and used to see them yearly in my own yard in Duluth. Now I'm lucky to notice a quick flyover—I haven't seen a single one at my feeders in more than a decade until just last month. In late December, a flock of 30 appeared at two of my platform feeders and on the ground beneath for a brief and shining moment. Since then, I’ve had brief visits of 1–3 several times.

The decline of Pine Grosbeaks in my yard is just one data point, but a combination of data from the Breeding Bird Survey and Christmas Bird Count indicates that populations in North America experienced a large and statistically significant decrease from 1965–2004—an overall decline of 27.6 percent per decade or 72.5 percent over the 40-year time period.

Pine Grosbeaks are suffering declining habitat where cutting down boreal forests—for paper, wood pulp, and Canada’s tar-sands oil industry—has decimated huge swaths of northern forest habitat. Deforestation is a major contributor to atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, so three things we can do in our personal lives that will help the grosbeaks—saving energy, using recycled paper (especially toilet paper), and avoiding wood fiber products—are also important for reducing our contributions to climate change.

One would think we humans would be happy to make such minor modifications to our lifestyles to protect our own futures as well as Pine Grosbeaks and other birds. Unfortunately, I'm afraid, one would be wrong.