Forty years ago, on December 20, 1981, the morning after the Duluth Christmas Bird Count, I was watching my feeders as I ate breakfast when what to my wondering eyes should appear but a Red-bellied Woodpecker. In The Birds of Minnesota, T.S. Roberts reported that Red-bellied Woodpeckers had first appeared in Minnesota in the early 1900s, and were breeding as far north and west as the Twin Cities by the 1930s. But 50 years after that, they were still a hotline bird in Duluth. Our phone was in the dining room so I could watch the bird as I dialed Kim Eckert. I said right that moment there was a Red-bellied Woodpecker at my fee— and heard a click. He was at my house 5 or 6 minutes later, but the bird had flown and neither of us saw it again.

In my first years of birding here in the Upper Midwest, Red-bellieds were much harder to see than the closely related Red-headed Woodpecker. I saw my first Red-headed on May 3, 1975, when I had just started birding. It was #20 on my life list, and I saw it regularly throughout that spring and summer, in many places.

It took two more months, until July 3, for me to see my first Red-bellied Woodpecker, on a field ornithology class field trip. That was #80 on my life list, and for the next few years, while we lived in both Lansing and then Madison, Wisconsin, I saw Red-headed Woodpeckers much more often than Red-bellieds.

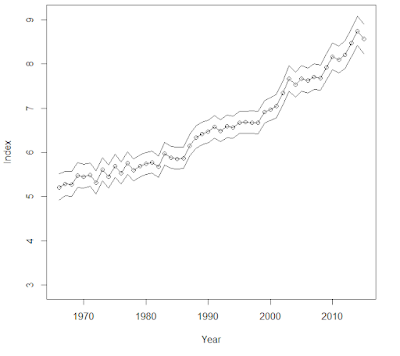

Now the tables have turned. Red-bellieds are thriving as well as expanding their range. According to Breeding Bird Survey data, their population has increased about 1 percent each year from 1966 to 2015.

Meanwhile, the same survey data from the same time period show that Red-headed Woodpeckers have declined by over 2 percent nationwide per year in the same time period, leading to a cumulative decline of 70 percent. The decline has been even more precipitous in Minnesota.

|

| Red-headed Woodpecker numbers in Minnesota from 1967-2015 |

It took time for Red-bellied Woodpeckers to become regular and then common in northern Minnesota. It wasn’t until the 1990s that I saw another in my own yard even as there were more and more reports in West Duluth. Then, in May 2002, a female turned up at my feeder every day for a week. The following March, she or another female showed up again and stuck around for two months. I named her Amanda.

|

| Amanda! I kept my mealworms in buckets of oatmeal. |

Whenever Amanda showed up at my window feeder, she’d gobble down 50 or more mealworms in a sitting, going through about five dollars’ worth every day. I was buying 20,000 mealworms at a time by mail-order—I ran out three times while Amanda was here. When she left in mid-May, even at a time when robins were taking plenty for themselves and their nestlings, the mealworms started lasting a lot longer again.

Soon Red-bellied Woodpeckers were regular year-round, especially in West Duluth. Mike Hendrickson and I, and probably a bunch of other birders, started reporting fledglings hanging out with adults, which meant they were definitely nesting around here. And then in 2016, I hit the jackpot. A pair nested right in my own box elder tree, fledging at least one baby—that was the first confirmed nest in St. Louis County.

Red-bellied and Red-headed Woodpeckers belong to the genus Melanerpes, along with the Golden-fronted Woodpecker of Texas...

...the Gila Woodpecker of the Southwest...

...Lewis’s and Acorn Woodpeckers of the West...

...and a dozen or so tropical species. Many Red-bellieds have a tinge of red on their bellies, but it’s fair to say that the species is rather poorly named—even those that do have the feature usually keep it hidden against tree trunks.

Oddly enough, Mark Catesby, the British naturalist who collected, illustrated, and named the bird on a trip to America between 1722 and 1726, drew it from the back, with that so-called red belly completely hidden.

Catesby’s book, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, published between 1729 and 1732, was the first published account of the species, so that was what Linnaeus used in 1778 when he assigned the bird its scientific name, Picus carolinus. (Picus, the genus into which he placed all woodpeckers, was named for Picus, a figure in Roman mythology who was transformed into a woodpecker by a witch named Circe.)

|

| Picus and Circe, by Luca Giordano |

The first American Ornithologists’ Union Checklist of American Birds in 1886 credited Linnaeus for the bird's original scientific name, but Catesby's original published account, used by Linnaeus, was the basis for the bird’s English name, which is still in use.

Like other woodpeckers, Red-bellieds eat a lot of insects, but also feed on plenty of acorns, nuts, seeds, and fruits. They are also known to eat lizards, nestling birds of other species, and even minnows. They’ve come to my feeders for peanuts, sometimes other bird seeds, suet, and those delectable if expensive mealworms. I’ve also seen them eating fruits in neighborhood buckthorns and Russ’s cherry trees.

This fall, both a male and a female were hanging out in my neighborhood, but oddly enough, whichever turned up first thing in the morning would be the only one I’d see all that day. But ever since the end of December, the female has been the only one I see, almost every day. This winter I’ve been plagued with starlings, which I don't want to subsidize, so whenever I’m at my desk and notice one in the tray feeder on my office window, I wave my hand and it flies off. The Red-bellied Woodpecker is far less skittish. She’s figured out that when I wave, the starlings fly off and she can eat in peace.

I still feel a thrill when I see her, and a bigger thrill when her eyes meet mine through the window. At one point I was thrilled whenever I saw a Red-bellied Woodpecker because they were so hard to come by. Now I'm thrilled because they're not.