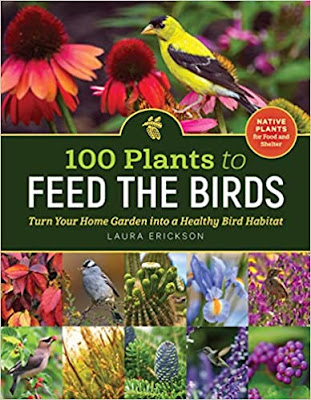

In May 2020, a month after my pregnant daughter and son-in-law refugeed from Brooklyn, New York, to our house during the pandemic, Deborah Burns, my editor at Storey Publishing, asked me to write a fourth book for them. (The previous ones are listed here.) The title would be 100 Plants to Feed the Birds, because this book would be part of a series that includes 100 Plants to Feed the Bees and 100 Plants to Feed the Monarchs. I said if I wrote it, I’d have to include a lot of plants that do not feed birds directly. A great many of our most beloved songbirds eat little or no plant material, feeding primarily or even exclusively on insects that depend on locally native vegetation.

But did it even make sense for me to write such a book? I’ve been monomaniacally focused on birds since 1975 and do little gardening. Russ and I have protected the native trees, shrubs, and smaller plants that support birds in our yard, and have planted a few native plants here and there, but that is small potatoes compared to some gardeners on my own block. How could I possibly be qualified to write this book?

In some ways, my misgivings pinpointed some of my strengths. Bird study may have absorbed me since college, but I took enough botany, forest management, wildlife ecology, entomology, aquatic entomology, and even horticulture courses to give me a broad background and a sense of what should be included and emphasized in this kind of book. My birding experiences have spanned all fifty states and at least a few pockets of Canada, and I’ve tried to keep up on important issues affecting birds, including habitat. From my first spring birding, I've paid attention to the specific plants some birds are strongly associated with. I am far from an expert on any of it, but when it comes right down to it, who is? There’s no way anyone can list exactly 100 of the best of anything without leaving out some things that others would include. For every plant an authority would include that I wouldn’t, they’d leave out a plant that other authorities thought was essential.

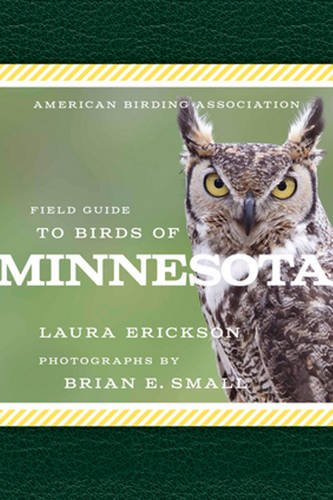

My internal debate reminded me of a previous book I’d done for a different publisher. When Scott & Nix asked me to write the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Minnesota, I refused, giving them half a dozen names of people I considered way more qualified than I was to write such a field guide. They kept coming back to me, and I kept giving them more names. I know I’m far from the state’s top birder in terms of species seen and quickness at identifying some species, and I’m less focused on identification than behavior, natural history, and conservation. And what the heck kind of birder could I be when I wouldn’t trade a season of watching a pair of Black-capped Chickadees nesting in my yard for wandering around to add much rarer birds to my state list?

But I had to admit, they had some good reasons to keep coming back to me. My previous books proved that I knew how to research, could be both concise and accurate, and worked well with editors. They could see from my having written The National Geographic Pocket Guide to Birds of North America that I could fit my words into a prescribed layout. I might not be among the very top birders in Minnesota, but I am good. And somehow, my not taking myself too seriously as an authority on bird identification worked in my favor for a book directed to beginners—the publishers knew I’d make birding friendly and inviting, and that I’d share the easy-to-make and even stupid mistakes I myself had made as a beginner and still make. When they agreed to expand the number of species covered to 300, I relented. I still had misgivings, but I’m very happy with how it all turned out and proud of my work.

This proposed book about plants and birds would take me even further out of my comfort zone than the field guide did, but Deb Burns’s faith in me was grounded in our having worked together on those three previous books for Storey. And the timing was perfect. The pandemic had eliminated all of my travel. I could focus pretty much entirely on this project for three months before Katie’s baby would be born, and I’d have a few more months while Katie and Michael were taking turns with parental leave before my grandma duties kicked into a higher gear. Even then, I could work evenings and during naps.

I spent a year and a half researching and writing, learning how much I did not know, and realizing that no matter where a reader lived in the continental U.S. or Canada, they'd need way more information that any single book could give them about their local situation. My treasured friend Ali Sheehey, an essential ally during my 2013 Big Year, took on the enormous task of researching and listing a native plant organization for every state and province, which makes the book ever so much more valuable and useful. I spent the next four or five months working with the publishing team as they made final edits, selected photos, and laid out the book, finalizing everything before it was sent off to the printers this past April. The book was officially “out” on December 20, meaning its gestation between final electronic version and printed reality was a little less than 9 months. My grandson was born a little past his due date, so the book’s and his deliveries averaged out perfectly.

I’ve been so consumed with being a grandma that I haven’t been paying proper attention to much else, so seeing my first copy was like seeing the book through fresh eyes, and I’m very happy with it. Plus it’s the only book in the known universe with a photo of Walter inscribed, “This book is dedicated to my grandson, Walter. May his generation inherit all the natural beauty and biodiversity that my generation did.”

I’m never comfortable promoting my own work, so this will probably be the last time I write a blog post specifically about the book, but in the coming weeks, I will be doing several posts about the plants birds depend on—material taken directly from 100 Plants to Feed the Birds. January is when many gardening catalogs arrive, and I hope some of the information will inspire readers to grow at least a few plants this coming year to support your favorite birds.

(Note: The book, a paperback, has a LOT of photos and a beautiful layout. The e-book works out very well on a computer screen, and probably works well on a tablet (I don't have one to test it), but is hard to read on my phone, and both hard to read and just black-and-white on my Kindle.)