This week I heard from Kelli Alseth of Proctor, not too far from Duluth. She's delighted to be hosting a Mourning Dove at her feeding station. She’s been sprinkling sunflower chips on a flat railing and her porch floor specifically for it, and that's where the dove spends most of its feeding time. She sent photos her husband Jeffrey took.

It’s very unusual for Mourning Doves to remain up here all winter—the vast majority head south. I’ve had them in my own yard only a couple of winters since we moved here 42 years ago. Duluth is north of the wintering range according to even the most up-to-date field guide, the 7th edition of the National Geographic, and the map on the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds website.

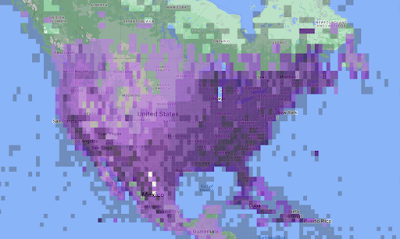

But Mourning Doves are functionally illiterate and never read that information when planning their travels. I saw one a couple of times at the very end of December, over a week after Duluth’s Christmas Bird Count. I would have loved to see one for the Count, but it wouldn't have meant much—13 were tallied by other people that day. As it turns out, Mourning Doves have been reported on 42 of the last 44 Duluth Christmas Bird Counts. Indeed, eBird’s map of Mourning Dove sightings from December through February extends well north of Duluth into Canada in the dead of winter.

|

| eBird map of Mourning Dove sightings, all years, between December and February |

So individual Mourning Doves do stick around up here just about every year, but there are excellent reasons that the vast majority head south. Unlike songbirds and even hummingbirds, Mourning Doves are vulnerable to frostbite, with a rich blood supply to their thick, featherless toes.

|

| I photographed this young Mourning Dove in July 2017. The fleshy feet are even redder when the outdoor temperature is cold and blood flows to the extremities. |

The way they protect themselves is to pig out a few times a day, stuffing not just their stomach but a large pouch in their esophagus called the crop, and then to roost in a secluded, sheltered spot for an hour or so, digesting their food as their warm tummy presses against their feet.

|

| The same young Mourning Dove is roosting comfortably. |

Thanks to their very short legs, very long tails, and habit of feeding on the ground and flat feeders, doves face another dangerous issue during sleet and ice storms: if their tail feathers get coated with ice, they sometimes become frozen stuck against the icy substrate. Over the years, I’ve heard from a few Wisconsin listeners about finding two or three Mourning Dove tails stuck to their platform feeders, or tailless doves visiting after such a storm. Tail feathers do grow back in, but with only marginal food availability in winter, this takes several weeks during which their compromised flight maneuverability makes them more vulnerable to predation. When we are lucky enough to host one or more Mourning Doves in winter or during harsh springs or falls, providing black-oil sunflower seeds and white millet in places where they can eat comfortably—on platform feeders or a sheltered spot on the ground beneath a thick conifer—is a mercy. Kelli Alseth appears to be a perfect dove hostess.

I usually don’t see Mourning Doves in my own yard until March or April, but I did see one on New Year’s Eve.

That made me hopeful that I’d add the species to my 2023 list on New Year’s Day. But no luck—I finally saw one on January 9 and two on January 12. They were a male and a female, which I could tell because one was noticeably larger than the other. Females are a duller brown with less iridescence, but I can’t see that without good light.

When Mourning Doves do winter up here, they usually visit more than one feeding station so they have backups if one food source dries up. The one they visit at first light in the morning and then as twilight sets in is usually their favorite. On Saturday, January 21, one visited my feeders on and off all day, and spent quite a bit of time roosting in the white spruce next to my home office, but it was nowhere to be seen the next morning.

Several people have feeders within a block of me, so I’m sure the two doves occasionally showing up here are more regular at at least one of those feeding stations than at mine. I’m very happy that Kelli Alseth’s visitor comes so reliably to her yard, and even more happy that her dove chose such a trustworthy person to count on.