Binoculars are essential equipment for birding, but a lot of people get frustrated trying to get birds in their binocular view before the birds fly. When I went out on my first birding jaunt, on March 2, 1975, I was using brand-new Bushnell 7x50 binoculars. They weren’t expensive even for back then, but with their huge field of view and extreme brightness, I never, even from the start, had trouble finding birds in them.

Those binoculars were a gift, and although they were extremely heavy, they were my passport to the whole new world of birds. A year later when I took my second ornithology class, I was asked to assist as a leader on some field trips, entitling me to use the university’s top-of-the-line Leitz 10x40 binoculars. They magnified birds 10 times rather than 7, and were smaller and lighter, the objective lens 40 mm instead of 50 mm. They were a noticeable improvement because of their superior manufacturing, but I had no trouble handing them back after each outing, happy to return to my own beloved pair.

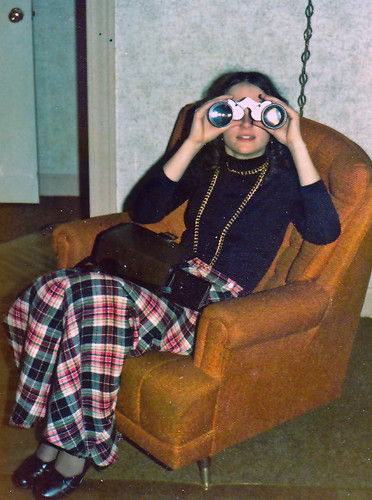

|

| Looking at my first Kirtland's Warbler through my trusty Bushnell 7x50s. |

Tragically, a few years later the cheap plastic neck strap snapped and my binoculars hit a rock, knocking them out of alignment. At this point I was ready for something lighter, but I made the mistake of going too far, getting Minolta 8x25 pocket binoculars. No one told me that the tiny objective lenses of pocket binoculars don’t let in enough light in early morning and late afternoon or in forested habitat, and are especially worthless for twilight or night birding, nor that the combination of higher power and narrower field of view would make it harder to find birds, though I used them so often that I quickly adapted to that. I do wish I’d known the longstanding rule that the diameter of the objective lens in mm should be at least 5 times the magnification power—that is, 7x35, 8x40, or 10x50.

Optics have improved enormously since the 1970s, but that 5-times rule still is very important for inexpensive binoculars that lack the sophisticated coatings of pricier models. Even in top-of-the-line models, the second number should never be less than 4-times the first.

For beginners, I strongly suggest a magnification of 7x or 8x. For any given model, that provides a much brighter view, less binocular-shake, lower weight, and a bigger field of view than 10x. It’s very important to use our binoculars a lot, pulling them up while keeping our eyes directed toward the bird. Practicing on stationary objects at first helps us discern whether the view through our specific pair of binoculars will land directly on, slightly above, or slightly below where our eyes were looking—this practice pays off when a good bird flies seconds after we spot it with our eyes. If you wear glasses, make sure the binocular eyecups are all the way down, putting your eyeglass lenses close to the binocular optical lenses. Those eyecups are designed to hold the optical lenses a precise distance from your eyeballs, but eyeglasses hold the binoculars about the right distance without the cups.

One very important rule for buying binoculars is to get the best model you can comfortably afford. Coatings and lens materials have improved enormously since I started out, and binoculars at every price point are better than they were half a century ago, but remember that for optics, the relationship between cost and quality is not linear. The jump in quality between $50 and $250 binocs is huge compared to the difference in cost. The jump in quality between $250 and $3,000 binoculars is huge, too, but not nearly as significant as the jump in cost. Top-of-the-line Zeisses or Swarovskis are definitely better than just about anything, but the biggest differences are hardly noticeable except for people who use their binoculars for long hours every day. For most of us, the difference between $250 binoculars and $3,000 binoculars could pay for a wonderful trip to see a lot of birds.

My focus has always been more on birds than on equipment, and I have no idea what products are out there anymore, so I asked one of my dearest friends, who is objective and knowledgeable about the current optics market, about his current recommendations. His top four favorites, all 8x42, as of February 2023 are:

When you’re in the market for binoculars, the very best way to test different models is at birding festivals. Representatives from manufacturers and retail companies encourage people to test their wares, often from an outside booth where you can look at real birds in natural conditions. If you know what your budget is, try to discipline yourself to test only models at or below your max.

Once you have the binoculars you'll be using for a while, the most important thing is to stop thinking about optics and just use them. After all, the whole point of birding binoculars is to focus on birds.

|

| I took this photo of Chandler Robbins's binoculars, which he was still very satisfied with, at lunchtime when we were in Guatemala in 2007. |