Twas the month before Christmas, when all through the house,

Not a creature was stirring—not dog, cat, or mouse.

Or maybe there was—I sure couldn’t tell.

My ears are so old that my hearing’s gone to hell.

So up to Essentia in my Prius I flew

To the audiology office up on Floor 2.

A hearing test taken, and a graph in bright red

Soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread—

Well, if sixty-two hundred in cash could be paid.

I can solve all my woes with a new hearing aid.

My life will be better, the audiologist said,

With bionic assistance stuck into my head.

Well, into my ears, where the problem began.

By spring, again kinglets could be heard in the land.

Her eyes how they twinkled. Her dimples how merry.

She made the bad news sound cheerful, not scary.

And I heard her exclaim ere I drove out of sight,

"Happy hearing to all, and to all a good night!"

Or did I hear that? You just never can tell

What a person can hear when her ears go to hell.

So I’ll scrape up the money—I hope I succeed—

Because hearing those birdies is something I need.

|

| Le Conte's Sparrow |

From the moment I started birding, I’ve loved learning how

to recognize birds by their voices. And I was lucky enough to have especially

acute hearing in the high frequencies. I had no trouble picking up Le Conte’s

Sparrows even at a distance when birders I was with couldn’t hear them at all,

or Golden-crowned Kinglets singing, or other high-pitched bird songs. To make

up for it, my hearing of low frequencies wasn’t very good at all—I’d need to be

way closer than other birders to hear hooting Great Horned Owls or drumming

Ruffed Grouse. Sometimes my body could feel the rhythmic drumming of a grouse

while my ears didn’t detect it at all.

|

| Golden-crowned Kinglet |

I taught an Elderhostel with a wonderful young guy named

Troy Walters at Trees for Tomorrow for several years. For the first year or

two, Troy was still learning a lot of bird songs, and I usually picked up on

birds before he did. But by the third year, we were hearing things

simultaneously, or took turns picking out things first. But in the past four

years or so, he was consistently hearing birds before me, and sometimes I never

did pick up on some songs. In 2012, for the first time ever, I watched a

Golden-crowned Kinglet in full song, beak open, breast heaving, but I never

heard a note. I was suddenly struggling to hear Golden-winged and Blackburnian Warblers, and had also been noticing that some songs well within my hearing

range are sounding different—losing the high frequencies means I’m missing out

on some of the harmonics of those songs, changing the overall tonal quality.

|

| Cedar Waxwing |

This fall, I used a Cedar Waxwing recording in a “For the

Birds” program I was producing. That’s a song I was still picking up on in the

field, and thought was still within my hearing range, but when I played the

recording, even at top volume, I couldn’t hear a whole section. That’s when I

knew I’d waited too long already. I made an appointment with an audiologist.

|

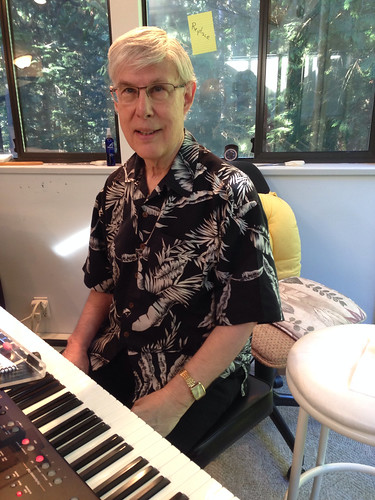

| Chandler Robbins |

Although the very thought of needing hearing aids is

sobering, I’m in excellent company. My birding hero of the universe, Chandler

Robbins, told me that he got hearing aids long, long ago. His younger brother,

the late Sam Robbins, was Wisconsin’s foremost birder, with legendary ears. As

Sam reached his 50s or 60s, he was starting to lose some of his high

frequencies, but refused to think about hearing aids until he and Chandler were

birding in Wisconsin one spring morning. Standing in one spot, Chandler could

pick out four Winter Wrens singing simultaneously, while Sam couldn’t hear any

at all—that's when he got his own hearing aids. I use a Winter Wren song as my phone’s ringtone, so if I lost that one,

I’d be in trouble in more ways than simply losing a splendid and favorite bird

song.

|

| Winter Wren |

I’m lucky that my excellent hearing lasted as long as it

has, and even now my 63-year-old ears still pick up on some sounds that others

miss, probably because I’ve been so focused for so long on noticing bird songs.

But my ears do need help now, at least if I’m going to keep mixing my own radio

programs and leading field trips and recording and listening to birds on my

own. Unfortunately, the kind of hearing aids that can help pick up the sounds I

need to hear are extremely expensive—a pair will cost $6,200. It would be much

less expensive to go with a cool new invention that simply lowers the frequencies

of high-pitched sounds so we can hear them within our hearing range, but to use

that, I’d need to relearn all my bird songs, and they wouldn’t sound the same. So

I’ll have to squirrel away all my earnings for a while to cover the hearing

aids, which I'll get in early April so my test period extends through warbler migration. I will commit when I know I can hear those warblers again. It's a heck of a lot of money, but it’ll be worth it for me to hold on a little longer to the bird songs

that have so enriched my life.

(This is not as bad as it sounds. Our insurance will cover some of the expense, and we'll put enough money in that "health savings account" thing so we won't have to pay taxes on the money for this. So don't worry about this!)