Back in the olden days, until I was was almost ten years old, Minnesota’s state bird was the goldfinch. But in 1949, someone got wind of the fact that the state legislature had never officially named it that. The goldfinch was also the state bird of Washington on the West Coast, New Jersey on the East, and Iowa in the middle, so the legislature named a committee to study the issue and come up with a state bird uniquely Minnesota’s. More than a decade later, they were still arguing the issue, but then the sudden widespread concern about pollution helped the Minnesota Ornithologists’ Union to persuade the decision makers to choose the Common Loon, a species dependent on water clarity and quality. I’m sure Minnesota’s being “the land of 10,000 lakes” helped, too.

Most states don’t put that much energy into thinking about their state bird. For a while, the state bird of North Carolina was, appropriately, the Carolina Chickadee, but because that tiny bird is sometimes called the “tomtit,” state legislators bristled when anyone called their state the “Tomtit State.” In 1943, when you’d think they’d have had more pressing matters to deal with, they changed their state bird to the cardinal.

Then there’s Georgia. No one was the least bit dissatisfied with the state bird they had in 1970, when state legislature jumped in anyway.

Way back on April 6, 1935, a proclamation by Georgia Governor Eugene Talmadge named the Brown Thrasher the Georgia state bird. But that was not official enough for the legislature, so on March 20, 1970, at the request of the Garden Clubs of Georgia, the state legislature named it the official state bird. The Joint Resolution of the Georgia General Assembly read:

Whereas, the Attorney General of Georgia has ruled in an official opinion that Georgia does not have an official State Bird; and Whereas, hitherto, the General Assembly of Georgia has made no such selection; and Whereas, since countless Georgians have always considered the Brown Thrasher as the official Georgia State Bird it is only fitting and proper that the Brown thrasher be given the recognition it is due.

(That same Joint Resolution also named the bobwhite Georgia’s official state game bird.)

The thrasher is such a beautiful bird with such a splendid song that it deserves state bird status. But oddly enough, many people don’t know anything about it, probably because it’s rather reclusive. It sings as loudly as the cardinal, from the same tippy tops of trees. No bird that was truly shy would sing so loudly, right out there in the open, but somehow even from its conspicuous perch on a bare branch as high as it can get in a tall tree, it’s almost always backlit, its long, slender body and tail, in a vertical stance, looking like a branch more than a bird, making it tricky for people to figure out where the loud song is coming from. This is how thrashers often manage to hide in plain view.

Cardinals sing their cheery song year-round; in spring, male Brown Thrashers quietly pick out a territory but then wait to sing until a female enters the scene. After a male has impressed one so that she selects him as her mate, he pretty much shuts up for the year as far as his loud, shout-it-from-the-treetops song, unless he needs to attract a new mate for a second nesting.

When they’re not singing, thrashers literally come down to earth, spending a lot of time on the ground and in low shrubs, but are far more reclusive than cardinals—people usually only see thrashers when they’re paying attention. They’re normally here in the Northland only in the warm months, though individuals overwinter occasionally in both Minnesota and Wisconsin. (I saw one at my favorite stomping grounds in Madison, Wisconsin—Picnic Point—through the winters of both 1978-79 and 1979-80.) Brown Thrashers live in Georgia year-round, giving people who spend time outdoors lots of opportunities to notice them despite their secretive ways.

Like the cardinal’s songs, Brown Thrasher songs are easy to identify, when you know what to listen for. Thrashers belong to the family Mimidae along with the Gray Catbird and Northern Mockingbird. All three have similar long, drawn-out songs, and all three incorporate some imitations of the sounds they hear, including cardinals and other birds, into their songs. Mockingbirds produce the most spot-on imitations, catbirds the fewest. The catbird song is long and disjoint, with occasional mews thrown in. The thrasher song is broken into words or short phrases, most repeated once. The steady string of paired sounds is easy to recognize, and has led to all kinds of mnemonics like, Hello! Hello! Who is this? Who is this? I should say! I should say! How’s that? How’s that? Mockingbirds repeat virtually all of their phrases, too, but we hear three, four, five, or more repetitions before the mocker goes on to the next phrase.

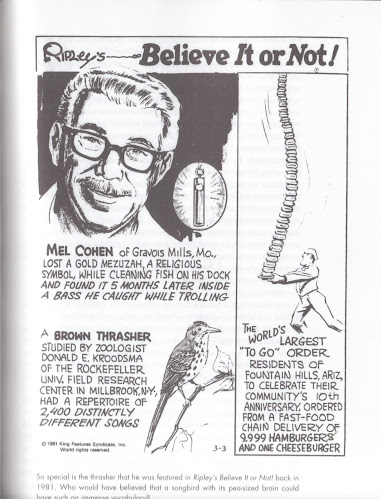

Both mockingbirds and thrashers sing a lot of different phrases in a single song, but the thrasher produces far more different songs than mockingbirds do. After analyzing hours of recorded songs and their spectrographs, Donald Kroodsma made it into Ripley’s Believe It or Not! in 1981 for establishing that one Brown Thrasher had a repertoire of 2,400 distinct songs.

It’s not just the size of its repertoire that makes it a favorite research subject. Researchers at Indiana University implanted tiny devices just beneath the two syringes of a Brown Thrasher, in its bronchial tubes. (Syringes is the plural of syrinx, a bird’s song box. It has two, one on each bronchial tube.) They showed that the air flow and muscles controlling the voice are operated separately for the two voice boxes, the left side generally producing the lower-frequency sounds and the right side the higher ones. Both contribute about half of the fantastically coordinated production of a single song. The Brown Thrasher was the very first species this kind of research was done on.

My all-time favorite authority on bird vocalizations, Don Kroodsma, writes and talks about the Brown Thrasher a lot. His most recent book, Birdsong for the Curious Naturalist, which came out this year, is filled with useful information for how to listen to birdsong, with links and QR codes taking us to hours and hours of Don’s professional recordings—he includes three hours and fifteen minutes just of Brown Thrasher songs, and explains in such clear and simple terms how he calculates the size of a single thrasher’s repertoire that I plan to calculate my own backyard thrasher’s repertoire based on my own recordings the next rainy day when I am stuck indoors.

I don’t envy Georgians for their state bird, but I’m sure glad at least one state chose it, and that this splendid bird spends time in my backyard, even if it’s mostly skulking around out of sight. My world would be a dimmer, duller place without it.