Yesterday, I got an email from someone named Dan who was in the middle of a nighthawk emergency. I virtually never give out my home phone number, but I made an exception because he sounded very nice and very anxious. And a few minutes later, my phone rang.

Dan lives in Jackson, Wyoming, where he had hit a nighthawk with his car. It fell, wings outstretched, on the road. A vehicle was approaching from the opposite direction but simply straddled it, so Dan turned around to check the poor thing out. It couldn’t fly, but didn’t seem to be wounded, so he brought it home and placed it in a small safe enclosure.

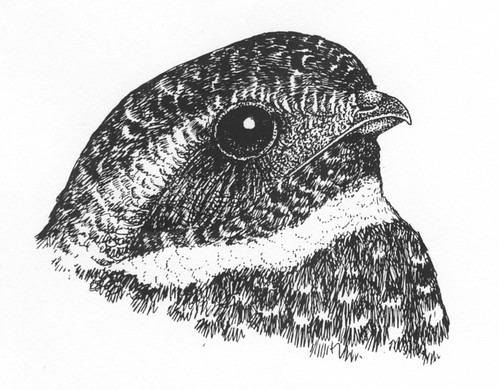

Not many rehabbers deal with nighthawks, and most of the ones that do handle only nestlings. This species is uniquely high maintenance because in the wild, once young birds fledge and for the rest of their lives, they eat only flying insects on the wing, their huge gaping mouth ideal for scarfing down moths, mayflies, winged ants, and other flying insects. A nighthawk flies into the insects at such a fast speed that the insects go down the opened throat without any effort at all. The nighthawk's vestigial tongue is just too tiny to get in the way. Its beak is tiny, too, and rather loosely attached to its huge mouth, so a nighthawk has no way of picking up food items, much less getting them to its throat to swallow. When a nighthawk has even a minor injury that grounds it, it’s pretty much doomed to starvation.

All baby songbirds and many other kinds of birds, including nighthawks, are fed by their parents, and in a rehab situation, they usually open their mouths readily to be fed by a rehabber. Adult birds usually can feed themselves as long as provided suitable food. Flycatchers and swallows usually take their meals on the wing but have no trouble picking up mealworms, crickets, and other insects when in captivity. Adult nighthawks simply cannot do that, and they also don’t have a clue that there is any other way of getting food in. When I’ve rehabbed them, it took time and patience to get them to open their mouths willingly—until then, I’d have to very gently tease open the mouth. And even then, with the food in their mouths, adults, especially males, had trouble swallowing it. Females are the ones who feed the young, so they still have working muscles in the back of the mouth and the throat which they use to regurgitate the food into their waiting babies. Adult males haven’t needed to swallow like that since they were chicks. For at least a couple of days and sometimes a week after they were eagerly opening their mouth to be fed, I’d still have to stroke their throat over and over to help them get the food down.

On top of this, nighthawks have fairly fragile wing and tail feathers but very short legs. In the wild, they can keep their feathers in good condition, but in captivity, the tips of those flight feathers often get frayed without protective sleeves over the tips. And care has to be taken to protect their feet—they can’t perch on normal bird perches, so care must be taken to keep whatever substrate they’re kept on clean, especially because at least once a day they produce a very liquid and caecal dropping which is quite messy. Rehab facilities are usually much too short-handed to be able to devote the time and attention, day after day, to that kind of high maintenance.

Anyway, Dan in Wyoming had called the nearest rehab facility which said they could just hold it for observation for a couple of days and then would have to have it euthanized. Dan googled nighthawk care and came upon a long blog post I’d written about it in 2012, which is why he emailed me.

Because this is nesting season, he was concerned about more than just this one nighthawk being lost if it was taking care of babies. Knowing only the females feed the young, I asked him if it was a male or a female, and told him he could tell by what color the throat was. He said it was brown, with some white on both sides. I focused on the brown and said it must be a female, but I should have realized that male nighthawks also have a brown throat—the white bib is not part of the upper throat area—so the bird was probably a male. But both of us thinking it was a female made us both even more concerned about what to do.

He said the bird seemed a lot more perky now. Sometimes it was spreading its wings on the bottom of the enclosure, but when I asked, he said it was holding them symmetrically, wasn’t listing to one side, and both eyes seemed fine.

Since the only realistic choices were to see if the bird could be released or to take it to the rehab center, he wondered if it would be worth driving back to the area where he’d hit it to let it go. It was 20 miles away, which meant a 40-mile round trip for nothing if the bird couldn’t take off, but if the bird was okay, he wanted it to have a chance to find its nest easily again. He was worried because he wasn’t sure of the exact spot, but said he could find it within five miles or so. I figured that should be plenty close enough for a bird that covers a lot of ground hunting. So that’s what he did.

Almost exactly an hour later, my phone rang again. Dan told me that when he let go of the bird, it fell on the ground, but he let it get its bearings and then prodded it gently a moment, and voila! It took off, circling higher and higher in the sky.

I haven’t rehabbed birds in over 20 years now. Many of the birds I took in were hopeless, and it grew more and more painful watching yet another one die from massive internal injuries after a cat attack, or after suffering extensive neurological damage from lawn pesticides. It was thrilling to hear about a happy ending right when I’ve been so sad and scared about how rapidly climate-change-related weather patterns have accelerated and how rapidly the COVID-19 Delta variant has spread. Yes, this was just one nighthawk, not a population, and won’t even begin to reverse the downward trend the species has suffered in recent decades, and certainly won't help with any other problems either. But Dan’s going to such lengths to help it made a huge difference in this nighthawk’s life, and in the lives of its mate and young, and that is something worth celebrating.